WORLDS WITHIN bodies, bedrooms, and breath

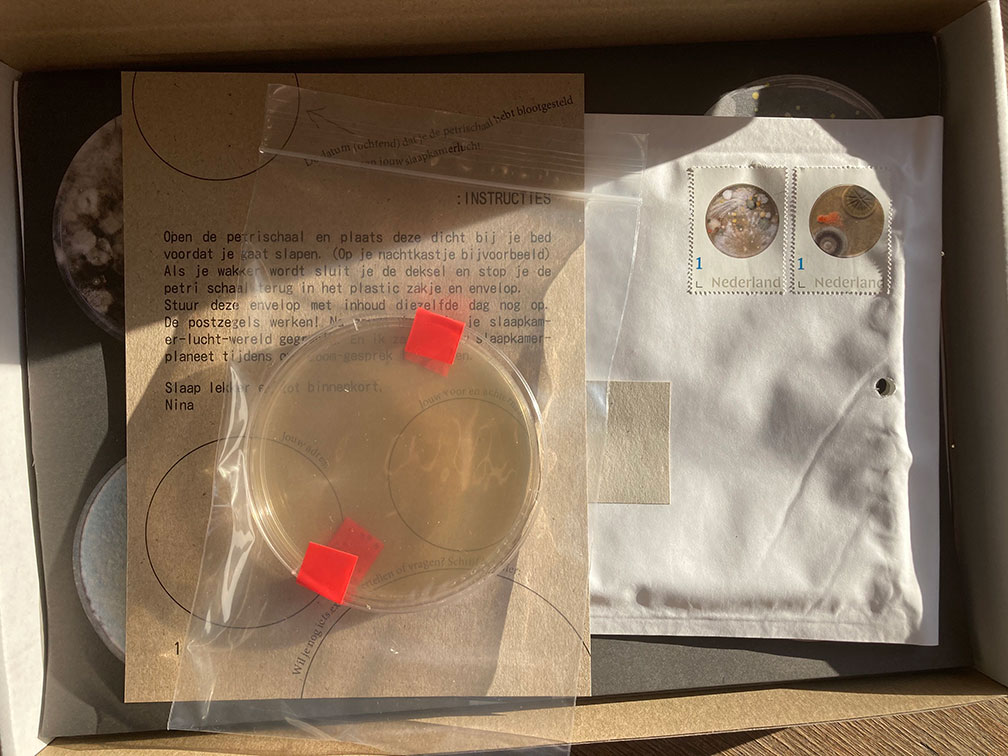

Installation, video, thesis, 2020 NL (Rietveld graduation project)

The world at large carries many worlds, most of which are invisible to us. This project aims to create an ‘Inview Effect’:

a sensorial experience of the inter-connections between individual worlds co-existing on different scales. How do we relate to the Earth, each other and the tiny ‘invisible’ non-human lives with whom we share our bodies, bedrooms and breath?

WORLDS WITHIN bodies, bedrooms and breath (ENG)

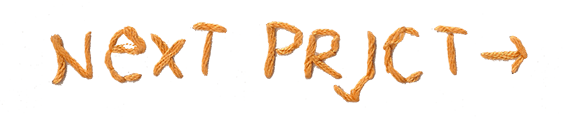

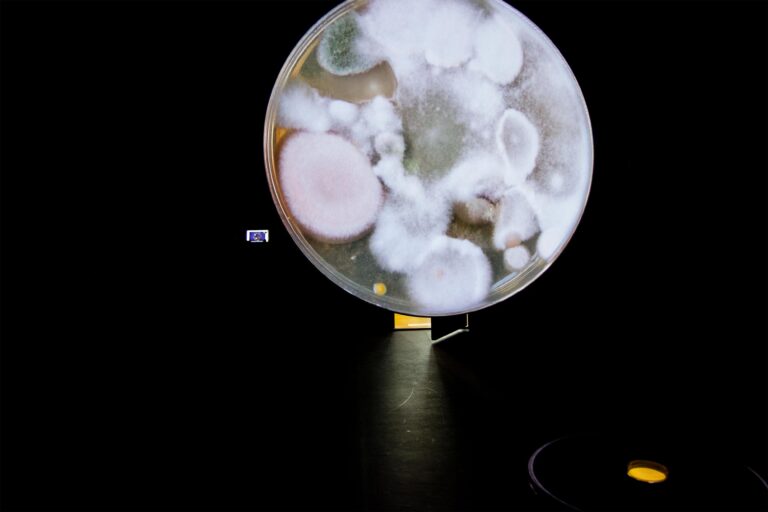

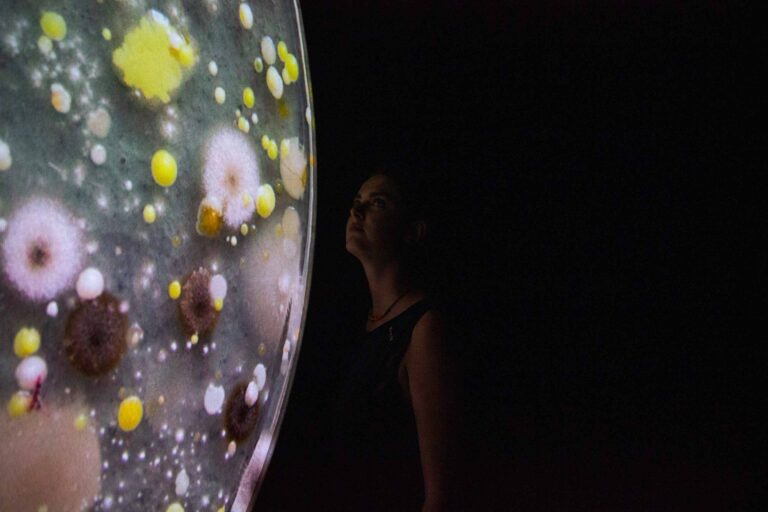

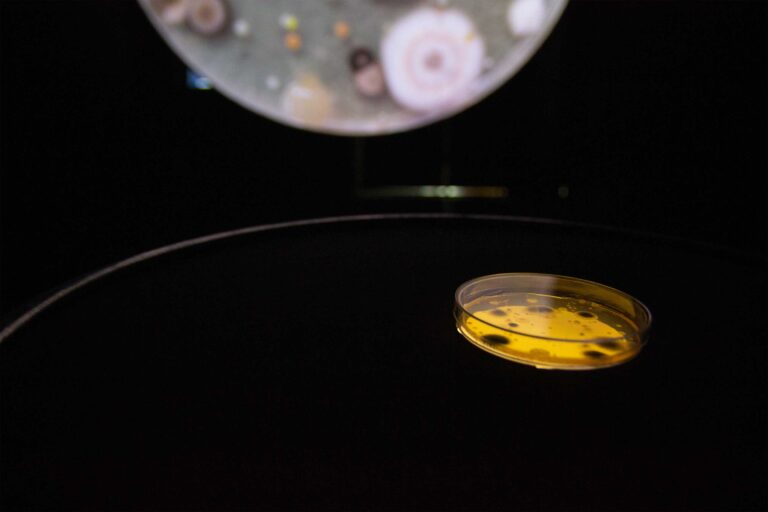

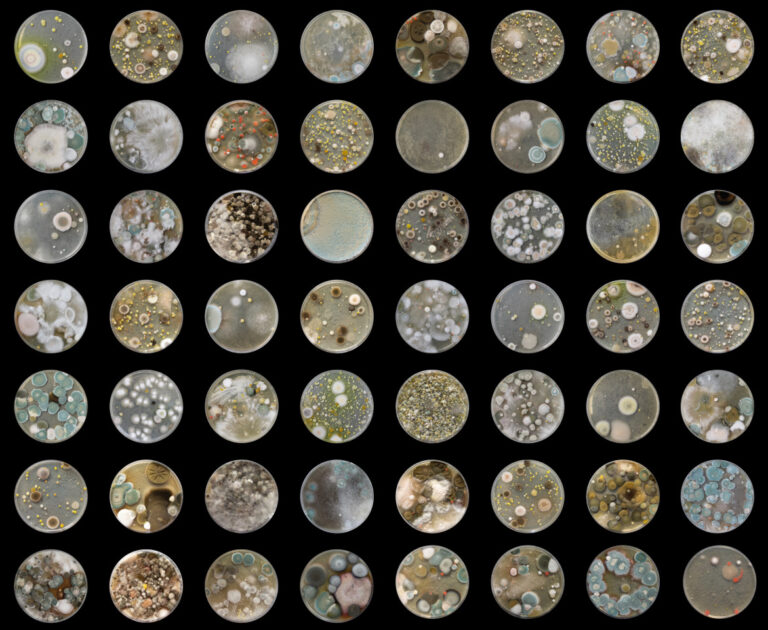

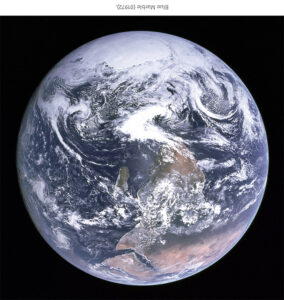

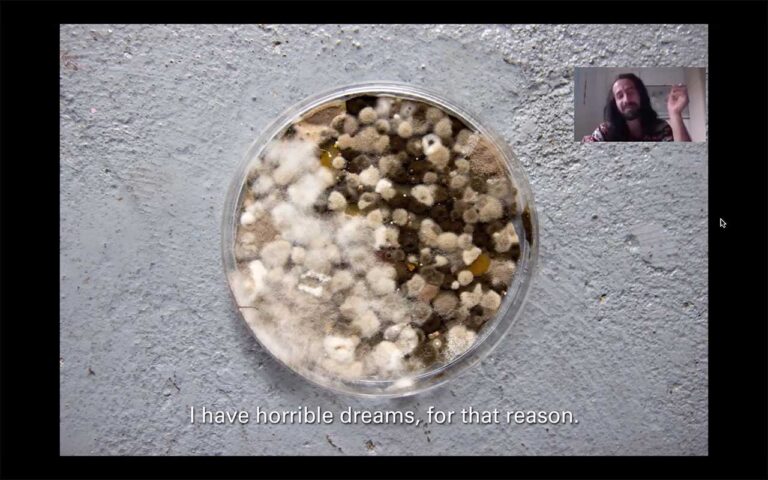

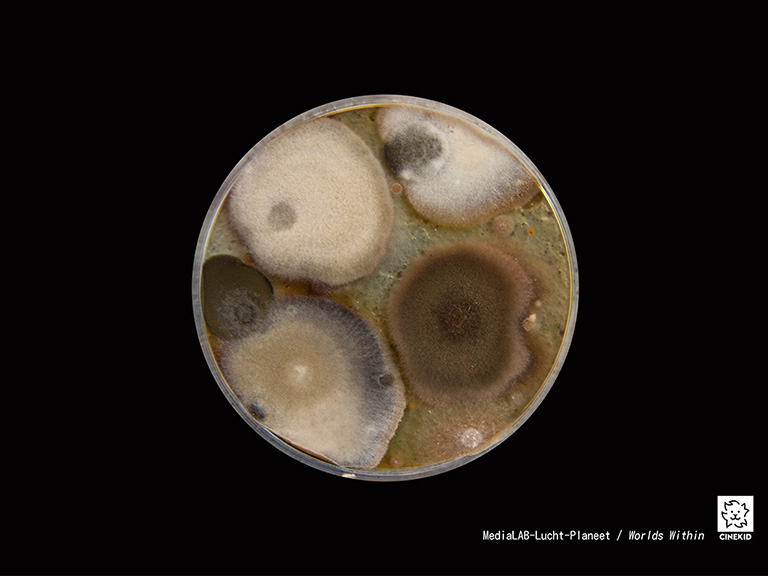

What is your personal take on global problems such as climate change, social inequality and environmental pollution? Although we can feel a sense of responsibility for the world in which we live, it is impossible for us to comprehend the world in its totality. Inspired by the ‘Overview Effect’, the profound shift in awareness and connection that astronauts feel when they see our ‘fragile’ planet from outer space, Nina wanted to create a similar experience from down below: an ‘Inview Effect’. She sent 48 packages with Petri dishes to people in quarantine, asking them to leave them out in their bedroom for a night. A week later, she photographed the result. By way of putting the human tendency towards superiority into perspective, and to reveal the mutual connection between the participants, Nina presents the cultivated ‘bedroom airs’ as enlarged projections reminiscent of a celestial body. In the accompanying video, she reflects together with the participants on their relationship with the ‘entire’ world, and with the ‘invisible’ non-human lives with whom we share our bodies, bedrooms and breath.

WORLDS WITHIN bodies, bedrooms and breath (NL)

Hoe verhoud je je als individu tot mondiale problemen als klimaatsverandering, sociale ongelijkheid en milieuvervuiling? Al kunnen we ons verantwoordelijk voelen voor de wereld waarin wij leven, het is onmogelijk de wereld in z’n totaliteit bevatten. Geïnspireerd door het ‘Overview-effect’, de diepe onderlinge verbondenheid die astronauten ervaren bij het zien van onze ‘fragiele’ planeet vanuit de ruimte, wilde Nina een soortgelijke ervaring creëren vanaf de grond, een ‘Inview-effect’. Ze verstuurde 48 pakketjes met petrischalen naar mensen in quarantaine met de vraag die voor één nacht bloot te stellen aan de lucht van hun slaapkamer. Zeven dagen later nam ze een foto. Om menselijke superioriteitsneigingen te relativeren en de onderlinge verbondenheid zichtbaar te maken, presenteert ze de gecultiveerde slaapkamerluchten als vergrote projecties die doen denken aan een hemelbol. In de begeleidende video reflecteert ze met de participanten op hun relatie met de ‘hele’ wereld en de ‘onzichtbare’ niet-menselijke levens met wie we onze lichamen, slaapkamers en adem delen.

Text from the BNO Yearbook ’20

How ‘WORLDS WITHIN bodies, bedrooms, and breath’ came into existence…

Worlds Within emerged after a year of intensive research and writing. In my thesis, ‘How to Breathe Together in a Changing Climate,’ I explored the potential of art to cultivate ecological and inter-relational awareness amidst the challenges of climate change, seeking to make a tangible difference: ‘How can new, radical imaginations help reduce the environmental destruction caused by human activity?’

To come to terms with my insignificant presence in the grand scheme of existence, I focused on something even smaller: the microbes that inhabit and surround us. Microorganisms illustrate the deep interconnectedness we share with the natural world. Without them we wouldn’t be alive, as they support all life’s essential chemical processes.

While the coronavirus pandemic began to spread in the Netherlands just two weeks after I completed my thesis, I embarked an endeavor to visualize our interconnectedness with the microbial world.

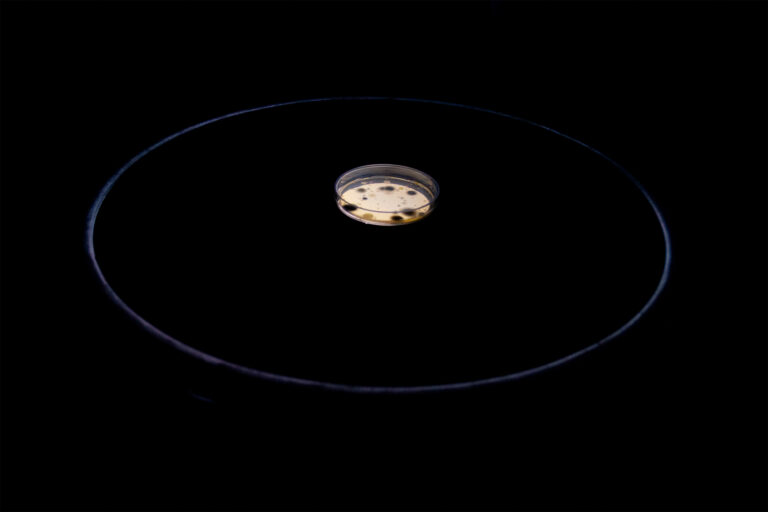

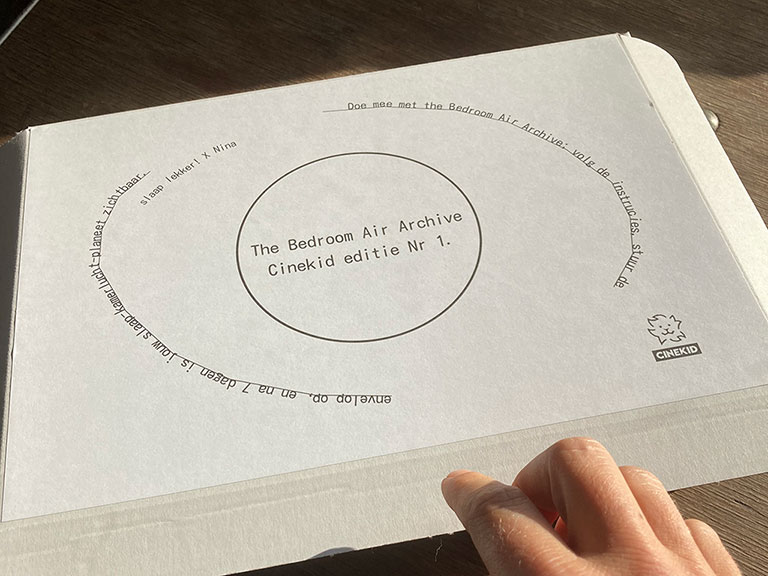

During the first Covid-19 quarantine period, I distributed Petri dishes to 48 individuals by mail, requesting them to expose the dishes to the air of their bedrooms overnight as they slept. After seven days, I photographed the microbial growth, thus creating an archive of the worlds we breathe while dreaming.

Inspired by the iconic Blue Marble— the only photo of a fully illuminated planet taken by human hands aboard Apollo 17 on its way to the moon in 1972, and the Overview Effect— a profound cognitive shift experienced by astronauts witnessing ‘our fragile’ Earth from space — I sought to evoke a similar experience, albeit from within, which I termed the ‘Inview Effect.’

I magnified the collected ‘bedroom airs’ into enlarged projections reminiscent of celestial bodies, aiming to challenge the narrative of human superiority on Earth and illustrate our planetary entanglement with other life forms.

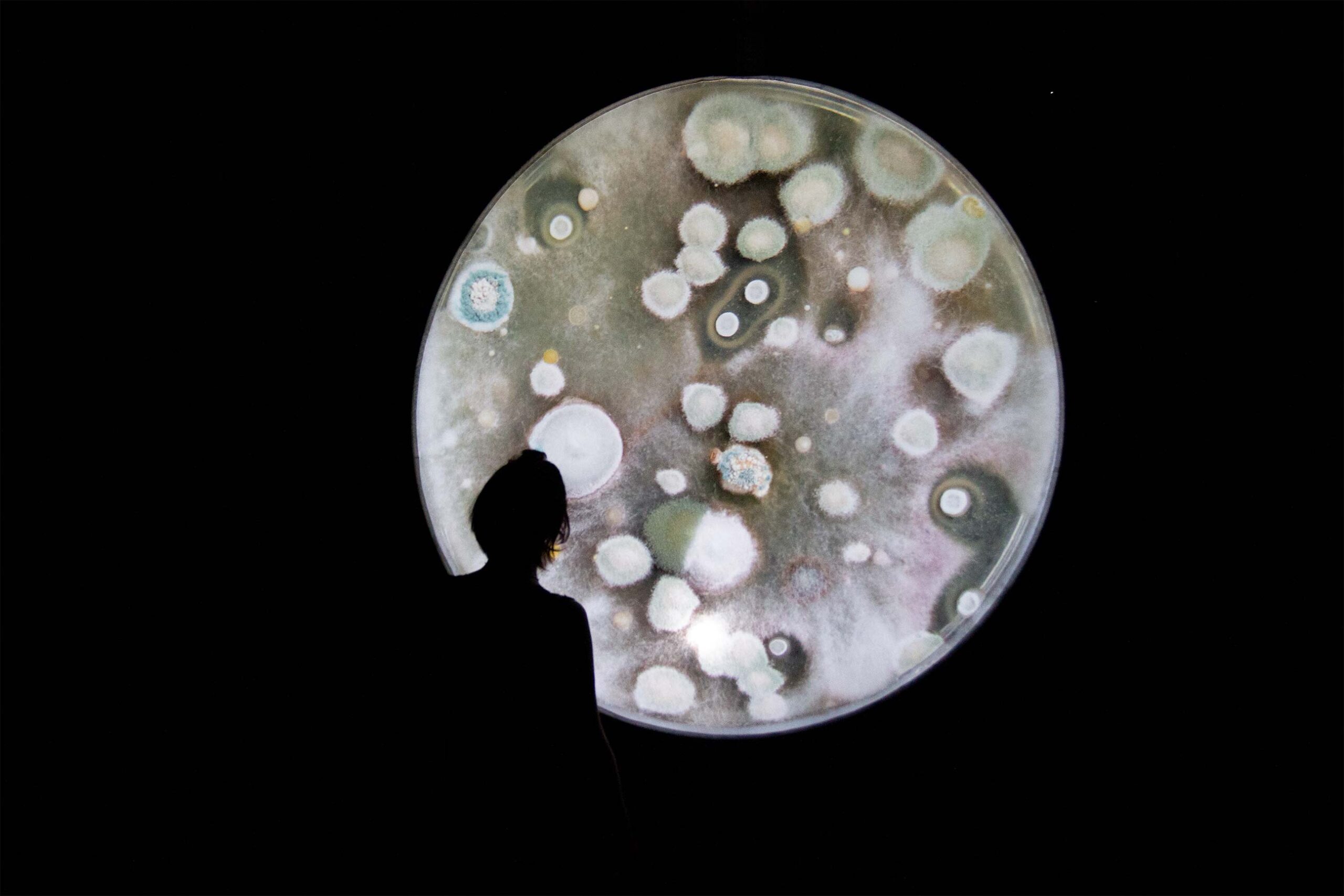

In the accompanying video, ‘Screen Reflections,’ (00:21:04 min) I engage in reflective dialogue with the participants on Zoom, exploring their connections with the ‘entire’ world, the influence of the Covid-19 pandemic on their personal lives and with the ‘invisible’ non-human entities with whom we cohabit—sharing our bodies, bedrooms, and breath.

”Do you recognise something of yourself in this world?”

Extract from ‘Screen Reflections’, (original is 00:21:04 min), 2020

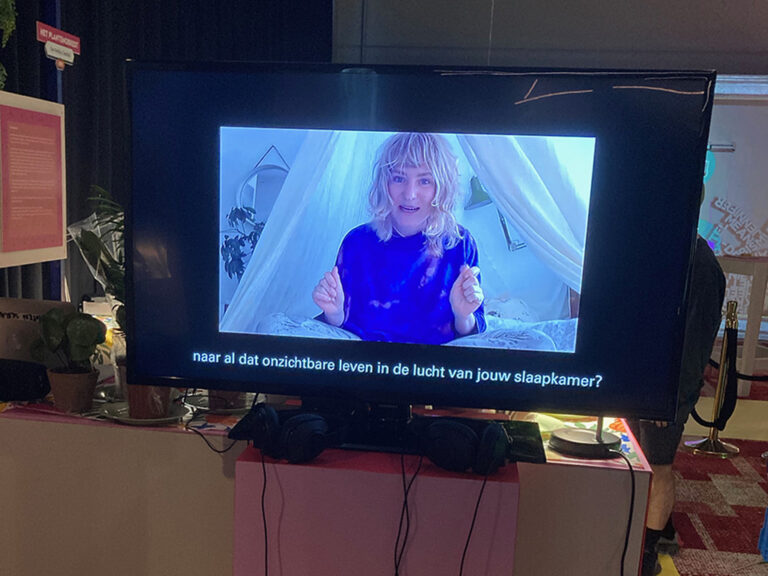

Worlds Within at ‘In Search of The Pluriverse’ curated by Sophie Krier and Erik Wong at Het Nieuwe Instituut, 2022

Pluriverse and Pluriversal Design

Drawing from other worldviews – mainly indigenous relational worldviews –, the pluriverse implies the existence of many worlds somehow interconnected.

”If a world of many centers is a world where multiple worlds can flourish, Pluriversal Design is a form of design that aims to nurture alternative ways of world-making, and to support to the construction of other worlds by people outside of the Center”.

– Arturo Escobar, Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds (Duke University Press, 2018)

In conversation with curator Sophie Krier about Worlds Within as part of the exhibition ‘In Search of The Pluriverse‘ at HNI, 2022

Photo’s: Aad Hoogendoorn

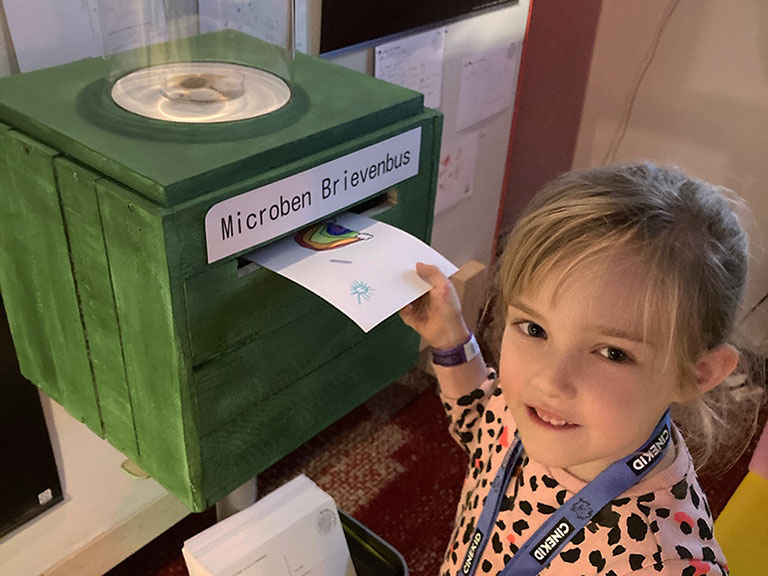

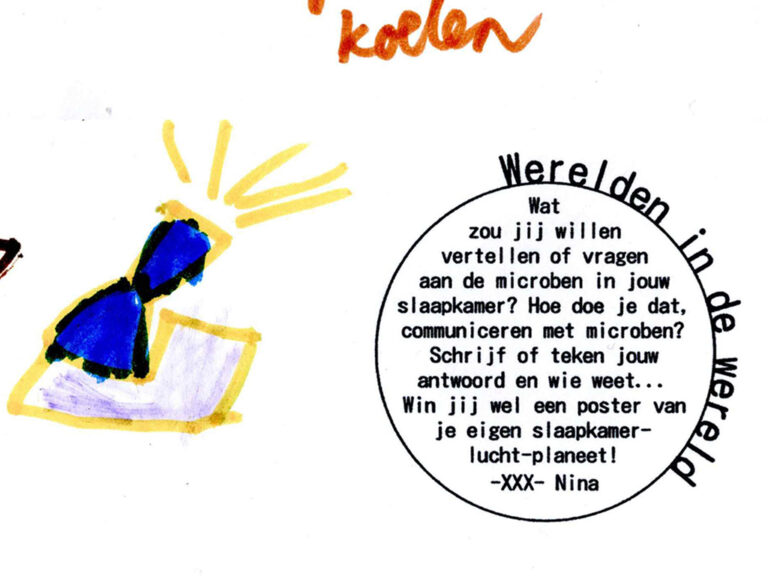

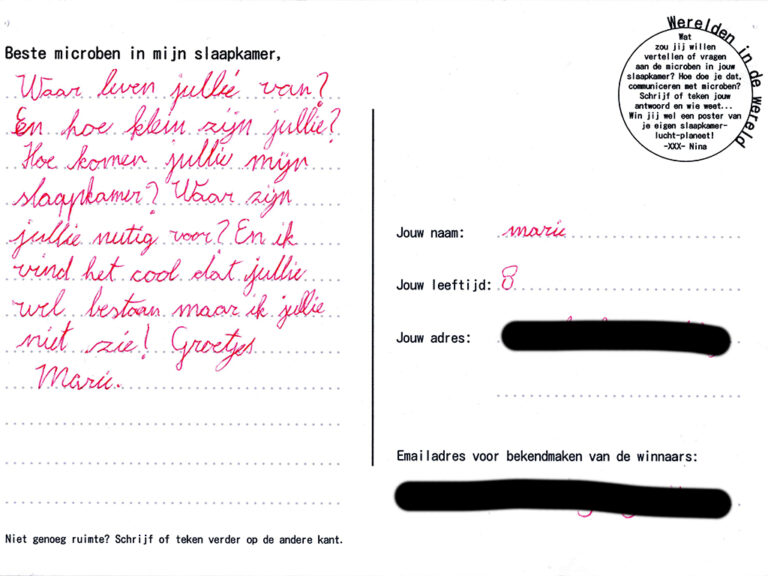

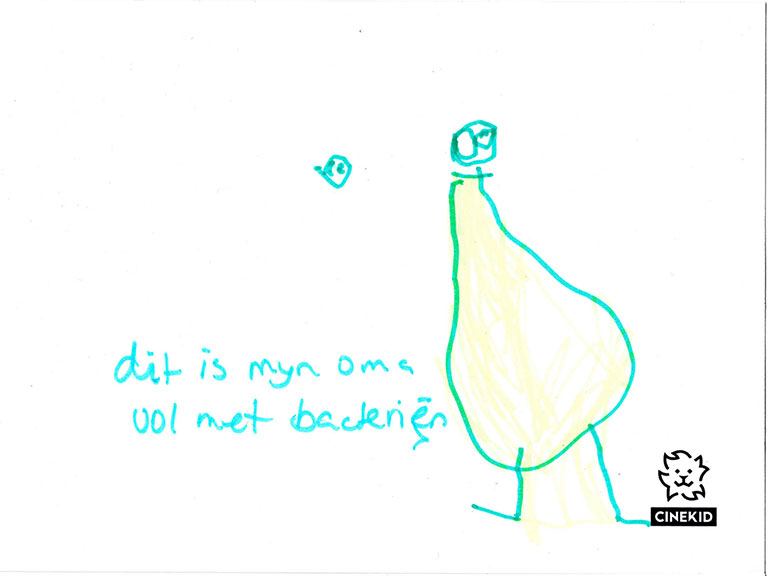

WORLDS WITHIN at Cinekid Media_Lab, 2021

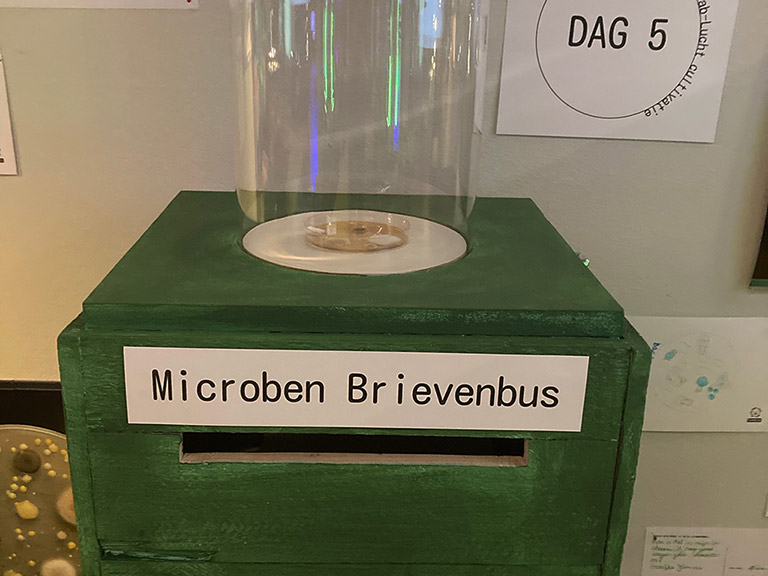

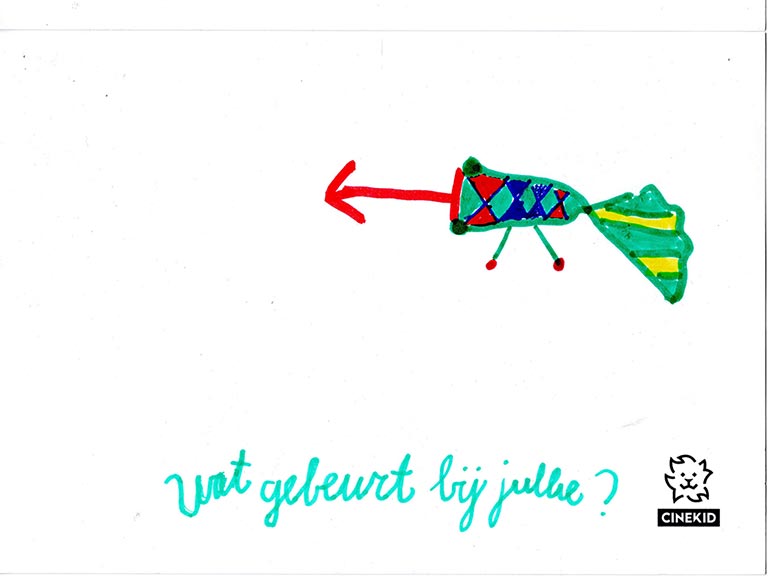

‘Letters to microbes’, Interactive installation and video.

What would you like to ask the microbes in your bedroom? And how would you communicate with them? During Cinekid Media_lab 2021, children were invited to write a letter to the microbes in their bedroom and bodies. After 10 days, the microbe-mail-box was full with more than 200 letters. The three most inventive letters received a poster of their own bedroom-air-planet. Additionally, I made a video with the Cinekid junior crew, which was on display at the installation.

“How to Breathe Together in a Changing Climate,” Thesis Synopsis

WORLDS WITHIN has been fuelled by an existential question: “How can an art practice help reduce environmental destruction and lessen the potential threat of an uninhabitable planet for humans and other species caused by human behaviour?”

An incredibly complex and big question, born out of feeling paralysed in the face of the apocalyptic narrative of climate change. However, I was determined to take action. While my thesis research didn’t provide a clear-cut answer, it led me on a journey across scales, revealing the intricate web of interconnections between worlds within worlds.

As I delved into writing my initial question branched off into a myriad of others: What kind of art could encourage social and environmental awareness? From which perspective is it most desirable to think and create: local or global? What are the limits of human knowledge? How are individual lives, dreams, and ideals influenced by collective narratives? What other life forms do I depend on? How can I visualize breathing, not just as a metaphor for life, but also as an act of sharing?

The further I zoomed out in an attempt to understand the whole world, the more entangled I became in the complexities of being ‘one’ breathing being among countless other life forms. We are all connected, sharing and depending on this planet for our lives. Yet, due to the limitations of our human senses, we’ve never truly seen this planet as a whole (taking 24 astronauts aside), besides through zoomed-out and scaled-down representations. This notion inspired me to reflect on the use of globes in visual environmental discourses.

Today, terms like globalization, global politics, and global warming have become deeply ingrained in the Western collective narrative. Satellite images of globes are often employed by politicians, corporate policymakers, scientists, and environmentalists to underscore the interconnectedness and individual responsibility for the future of our planet. While seemingly desirable, the globe model can render individual lives invisible, and a unifying global narrative can be dangerous when it overlooks individual differences.

For example, when corporate policymakers use this narrative to disavow their responsibility for actions that impact the environment on a large scale, by making us believe that we are all evenly responsible for climate change, as T.J. Demos argues in his book Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and Environment Today (2017). The assumption that ‘we’, the whole of humanity, are the cause of the eco-catastrophe happening needs to be questioned. Who is the ‘we’? Who is responsible for what? Who is operating on which scale?

Furthermore, imagery of globes can perpetuate the illusion of human (Western) mastery over the planet. It’s noteworthy that the earliest surviving globe was designed in 1492, the same year Columbus embarked on his journey to the Americas. Globes were often bestowed upon rulers as gifts, symbolizing their control over their land. Yet, the unforeseen consequences of our attempts to dominate the earth, such as climate change, challenge the notion of our control.

Instead of subscribing to a collective narrative focused on exerting dominance over our environment, we need more inclusive narratives that acknowledge the importance of non-human lives, as our co-existence is vital to our survival. For example, we share what are commonly perceived as our most private spaces—our bodies and bedrooms—with numerous other life forms. An adult person carries between 1,5 and 2 kilograms of microorganisms in their body, essential for vital processes yet capable of causing illness to the point of death.

This notion gained greater significance since the emergence of a microscopic virus that has disrupted global systems, illustrating how small ‘invisible’ beings can influence our world at large. While I had just finished my thesis, two weeks before the COVID-19 pandemic began to spread in the Netherlands, it is worth mentioning that the pandemic underscored the interconnectedness of life on Earth, which raises questions about human control over our environment.

The Corona crisis and the climate crisis emphasize that we are all in this together, interwoven in complex ecosystems with unforeseen consequences. Donna J. Haraway aptly describes this interconnection in “Where Species Meet,” (2008) highlighting the intricate layers of reciprocal complexity shaping our world. ‘’We find ourselves in a knot of species co-shaping one another in layers of reciprocating complexity all the way down.’’ (P 42)

I was surprised to learn that there is only one photograph taken by human hands of a fully illuminated Earth in our collective image archive, known as the ‘Blue Marble.’ Captured during the last lunar mission in 1972, this image has become one of the most reproduced in history.

The ‘Blue Marble’ inspired me to explore the experience of astronauts and the ‘Overview Effect.’ Seeing Earth from outer space evokes interconnected ‘one-world feelings’ and a renewed sense of environmental responsibility. This cognitive shift has been defined as the ‘Overview effect,’ prompting me to consider if a similar experience could be created from a local perspective on the ground.

Could I craft an ‘Inview effect’—an experience that evokes ‘one-world feelings’ while acknowledging individual differences and including other life forms, honoring our co-existence?

Trace; find or discover by investigation; uncover; in hindsight; patterns; colours; connections; (in)visible; imprints; indications of existence; map; worlds; in transformation;

Trace; find or discover by investigation; uncover; in hindsight; patterns; colours; connections; (in)visible; imprints; indications of existence; map; worlds; in transformation;

Want to read my thesis? Click on the image above.

”I love the fact that human genomes can be found in only about 10 percent of all the cells that occupy the mundane space I call my body; the other 90 percent of the cells are filled with the genomes of bacteria, fungi, protists, and such, some of which play in a symphony necessary to my being alive at all, and some of which are hitching a ride and doing the rest of me, of us, no harm. I am vastly outnumbered by my tiny companions; better put, I become an adult human being in company with these tiny messmates. To be one is always to become with many.”

– Donna J. Haraway, When Species Meet, University of Minnesota Press 2008, (p. 4)

“In a world conceived as a globe, as Heidegger remarked when he first saw a picture of the earth photographed from space, there is nowhere for us humans to be. The earth affords habitation, the globe does not and while we may accept some responsibility for the global environment it’s not one which we feel we can belong.”

– Anthropologist Tim Ingold

“In a world conceived as a globe, as Heidegger remarked when he first saw a picture of the earth photographed from space, there is nowhere for us humans to be. The earth affords habitation, the globe does not and while we may accept some responsibility for the global environment it’s not one which we feel we can belong.”

– Anthropologist Tim Ingold